IM doc pt20

Nov. 2nd, 2021 04:24 pmFrom Tragedy to Hesitancy: How Public Health Failures Boosted COVID-19 Vaccine Scepticism

Yves here. This post confirms what IM Doc has been saying for some time. For instance, via e-mail in April:

As a young child, I saw my father [a public health officer] struggle through the Swine Flu of 1976 and the vaccine debacle that accompanied that era.

As I grew older, and especially once I entered medicine, he had several heart-to-heart talks with me about a career in Medicine and by extension public health. I can summarize what he told me in two large thrusts. 1) Integrity, truth, and honesty is EVERYTHING in public pealth. Once squandered, it will never return. 2) Public health is 10% science and 90% psychology. Do not ever forget that. You will get nowhere by screaming SCIENCE SCIENCE SCIENCE and you will certainly get nowhere by flashing credentials. And you must have an acute awareness of panic, fear and anxiety. They change everything and your response must always take that into account.

Here, initial Covid failures and the elite pretense that they could just carry on as if that were a thing of the past, as opposed to admit to the errors and discuss how they planned to do better going forward, has exacted a price in terms of trust, as this post below explains.

By Geraldine Blanchard-Rohner, Senior Pediatrician and Immunologist, University Hospital Geneva; Bruno Caprettini,SNF Ambizione Fellow, Department of Economics, University of Zurich; Dominic Rohner, Professor of Economics, University of Lausanne; CEPR Research Fellow; and Hans-Joachim Voth, UBS Professor of Macroeconomics and Financial Markets, Department of Economics, Zurich University. Originally published at VoxEU

As COVID-19 vaccination programmes accelerate across the industrialised world, vaccination hesitancy is rapidly emerging as a key challenge. This column explores the relationship between pre-pandemic intensive care unit capacity and attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine in the UK. Despite widespread pre-pandemic scepticism about vaccines in general, willingness to become vaccinated against COVID-19 overall was strikingly high, even amongst those who rejected vaccines before the pandemic. The results point to a surprising synergy: where the emergency care systems of public healthcare providers were less strained during the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic, vaccination hesitancy is systematically less today.

Since February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has cost millions of lives and has affected almost every aspect of economic, social, and cultural life – from stock markets to inflation, schooling, inequality, and the gender division of labour, to name but a few (Yeyati and Filippini 2021, Burgess and Sievertsen 2020, Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020, Capelle-Blancard and Desroziers 2020, Sevilla and Smith 2020). Infection rates surged around the globe, and medical systems came under increasing strain.

In recent months, vaccination programmes have accelerated across the industrialised world. With supply problems increasingly solved, vaccination hesitancy is rapidly emerging as a key challenge on the path to herd immunity (Troiano and Nardi 2021, Dror et al. 2020). Given the high infectiousness of new variants, vaccine take-up amongst adults will have to reach particularly high levels for COVID-19 to be brought under control.

Our new study offers novel lessons about the drivers of vaccine hesitancy (Blanchard-Rohner et al. 2021). A previously overlooked factor can be crucial, namely, the efficiency and success of public healthcare provision during the pandemic. When the pandemic first broke out, intensive care units (ICUs) in many countries and regions were quickly overwhelmed, resulting in high mortality rates.

Using newly collected survey data from the UK, we show that success in providing emergency care during the dramatic initial phase of the pandemic is a powerful predictor of people’s readiness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Where the NHS was quickly overwhelmed, with overcrowded ICUs and high COVID-19 fatality rates, the willingness to become vaccinated is markedly lower.

Our findings suggest that there is an important, neglected synergy between an effective healthcare response in the early phases of a pandemic and the public’s trust and willingness to use novel treatments like the new COVID-19 vaccines.

We conducted two waves of interviews about vaccination attitudes in a nationally representative sample in the UK – in the autumn of 2019, before the pandemic; and in April 2020, during the first wave. We interviewed the same respondents, which allowed us to track changes in attitudes over time. These changes we then correlate with the quality and effectiveness of emergency care in different areas of the UK. In total, we had 1,653 respondents in the first wave, of which 1,194 participated in the second wave.

Respondents included a sizeable share of vaccine ‘hesitants’ and respondents who outright reject vaccinations – participants who in the fall of 2009 had declared that it was better for children not to receive vaccines, or that vaccines cause severe adverse effects including autism. We estimate that 12% of respondents reject vaccinations altogether and another 36% are sceptical. Only 52% of participants were strongly positive about the effects of vaccines in general prior to the pandemic.

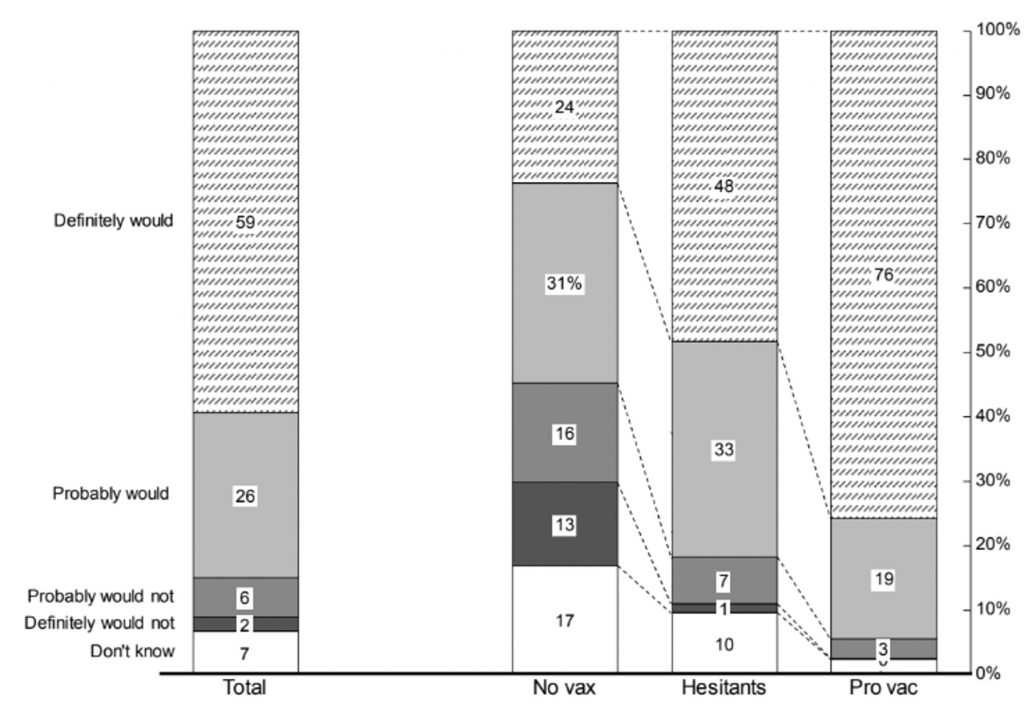

Despite this widespread vaccination scepticism, willingness to become vaccinated against COVID-19 overall was strikingly high – some 85% of study participants said that they were definitely or probably willing to become vaccinated. Remarkably, even amongst those who reject vaccines or are hesitant, 55–81% are willing to participate in COVID-19 vaccinations (Figure 1).

Figure 1 COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and general vaccine attitudes

Source: Blanchard-Rohner et al. (2021)

Notes: The figure shows responses to the question: “If a vaccine against COVID-19 became available for everyone tomorrow, do you think you would or would not get vaccinated?” The bar on the left reports the breakdown for all respondents of the April 2020 survey (N = 1194). The other 3 columns report the breakdown for three categories of respondents: “no vax” (N = 148), “hesitants” (N = 431) and “pro vac” (N = 615). We assign respondents to one of these categories using ther answers to the question on general vaccination attitudes. See Section S.2 in the Supplementary Materials for details on the construction of these categories.

Several interpretations of this fact are possible. Vaccination sceptics may feel that most diseases against which vaccines are routinely used are not terribly harmful; faced with a potentially deadly illness, they change their mind. Alternatively, sceptics may have updated their beliefs in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 24/7 media coverage of the disease, its consequences, and the need for a vaccine.

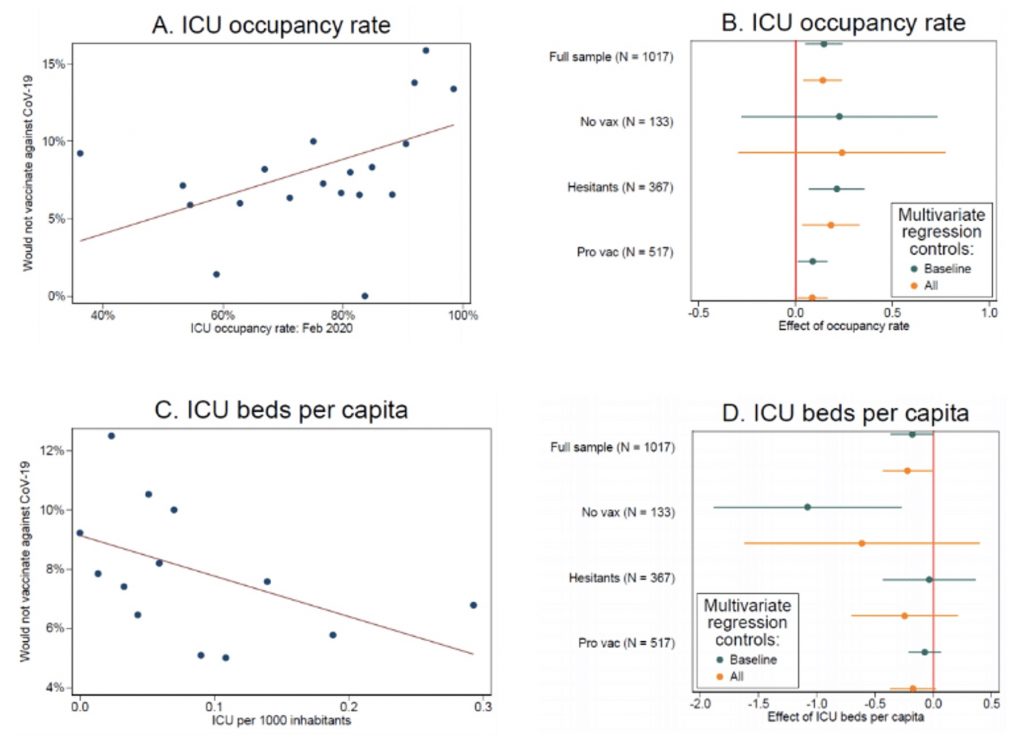

Our second main finding involves the role of public health provision. Before the arrival of vaccines, the availability of ICU capacity was a key determinant of mortality – where intensive care beds were missing, death rates spiked. We exploit the fact that various areas of England had different pre-COVID-19 levels of ICU coverage. This, in turn, meant that NHS hospitals in some areas ‘ran out of road’ much faster than others once the pandemic hit.

When we examine simple correlations, we find that low ICU capacity during the first wave of the pandemic is associated with lower vaccination willingness. This is not a result of pre-existing attitudes but a direct consequence of how vaccination hesitancy changed during the pandemic.

Panel A of Figure 2 plots vaccine hesitancy against ICU occupancy rates in February 2020, before the UK saw its first major spike in cases. The higher pre-crisis capacity usage, the greater hesitancy was by April 2020. In other words, where exogenous variation in ICU demand pre-epidemic had reduced spare capacity in ICU units, the pandemic struck harder.

Figure 2 ICU availability, perceived risk and unwillingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19

Source: Blanchard-Rohner et al. (2021)

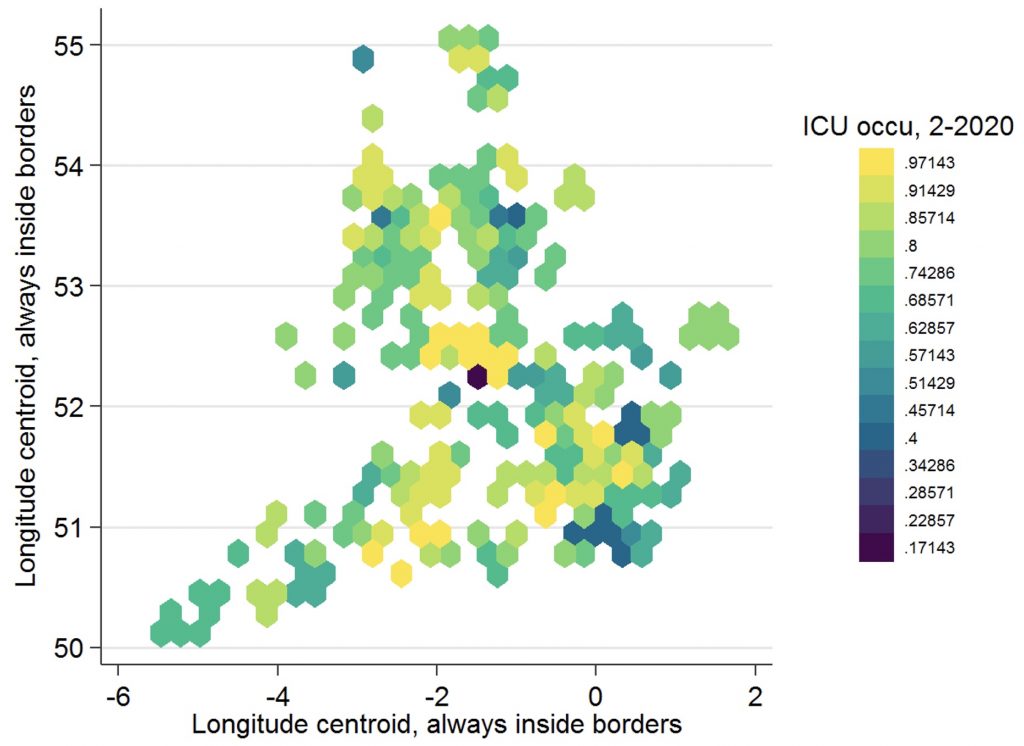

This failure to provide effective support was not a result of structural under-provision in certain areas. No such pattern is visible if we use, say, ICU occupancy half a year earlier (October 2019), strengthening the case for a causal interpretation of our finding. Figure 3 gives an impression of the variation in ICU occupancy across Britain on the eve of the pandemic’s first wave, in February 2020.

Panel B of Figure 2 shows the same exercise for different groups, and after controlling for observables. We find positive effects throughout. The analogous pattern is visible if we use the number of ICU beds per 1,000 inhabitants as an indicator of public health resources.

Figure 3 Variation in ICU occupation across Britain in February 2020

Source: Using data from Blanchard-Rohner et al. (2021).

Policy Implications

At first pass, many observers could think that public health resources like ICU capacity and vaccination campaigns are substitutes – countries with high capacity to deal with severe cases might be able to cope with lower rates of vaccination take-up. However, our results point to a surprising synergy: where the emergency care systems of public healthcare providers were less strained during the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic, vaccination hesitancy is systematically less today.

While generally high rates of support for vaccination make it more likely that herd immunity can be reached, our findings suggest that generous provision of spare emergency capacity can generate additional benefits, in the form of the public’s greater willingness to become vaccinated.

See original post for references

RE: ESCAPING INTO BRITISH HUMOR IS THE PERFECT BALM Crime Reads. I adore Wodehouse, not only for the laughs and the madcap plots but also for his limpid prose.

IM Doc says:

The next post is pretty long so it'll be posted here separately to spare my readers.

On this:

“WA: “Almost all new COVID cases in King Co. are from unvaccinated people, experts say” [KOMO]. “The good news: cases and hospitalizations are dramatically down since the peak of the 4th wave in late April. The bad news: 97% of the new Covid-19 cases—are coming from unvaccinated people.””

I’m not sure you can trust this kind of data anymore with the updated guidance from the CDC as of May 1st.

From the CDC website:

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/health-departments/breakthrough-cases.html

“As of May 1, 2021, CDC transitioned from monitoring all reported vaccine breakthrough cases to focus on identifying and investigating only hospitalized or fatal cases due to any cause. This shift will help maximize the quality of the data collected on cases of greatest clinical and public health importance.”

So if someone is vaccinated and tests positive, they aren’t counted as a COVID case unless they are hospitalized or die. You will only have 2 kinds of COVID cases. 1. Any positive test from an unvaccinated person or 2. A vaccinated person who is hospitalized or dies which should be unusual if the vaccines work as advertised.

Right — the CDC is leaving it up to the states to decide whether or not they test and track vaccinated people who come down with mild or asymptomatic Covid. And the KOMO article never defines what constitutes a new case among unvaccinated people. Is it just people that are hospitalized or die, or does it also include asymptomatic and mild cases? Are we comparing apples to apples or what? Another fine example of at best, sloppy reporting. At the worst? Fitting the facts around a desired narrative.

Thanks for the translation from CDC-speak.

Thank you for pointing this out. The US insistence of redefining “pandemic” at every turn…. that’s the one weird trick that really did us in.

Not just the US. Last year when the Coronavirus was starting to rage, not only did the WHO refuse to call it a pandemic, but they actually removed the word ‘pandemic’ from their official lexicon that they used. Several weeks later they re-instated it and then came out and called it a pandemic but that was nothing short of criminal behaviour that. Totally unforgivable.

The article never comes out and says what the actual number of new cases is either.

Looking at the King County Covid Dashboard, yesterday, June 2, there were no new hospitalizations and no new deaths.

The 7-day averages of both hospitalizations and deaths are also rapidly falling: Hospitalizations dropping from 9 or 10 per day on 5/27 to zero yesterday and the 7-day average for deaths at about .6.

Not to say new cases aren’t worrisome, but the article leaves out a lot of facts.

I am also always on the lookout for manipulation when any statistical information in presented as a percentage. (a 97% drop, etc). That is how statistics can be easily manipulated.

Please note – this article and many others does exactly that. I would feel much better if just plain raw numbers were reported.

Look through the ads of any Big Pharma marketing campaign. You will note instantly that everything is reported in %. There is a reason for that.